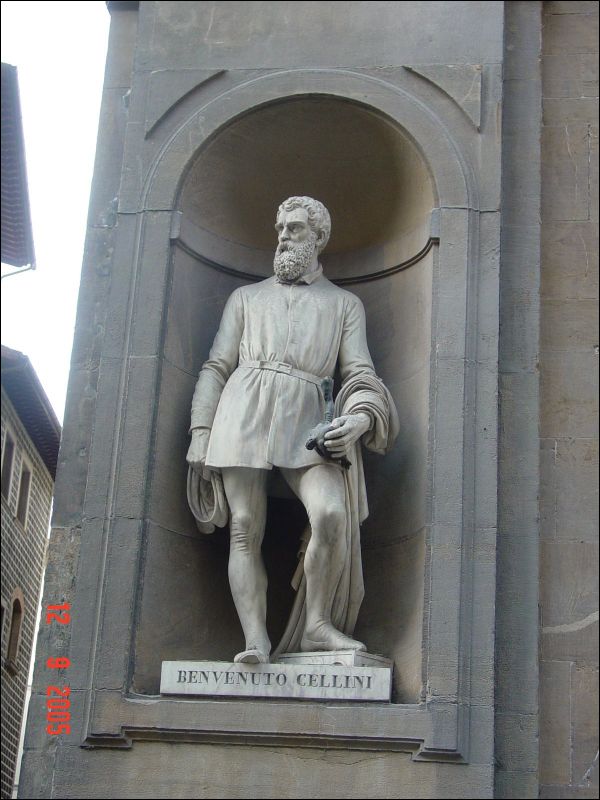

Ark and Laura in Florence 2005 (122 of 172)

![[First]](bw_first.gif)

|

![[Prev]](bw_prev.gif)

|

![[Index]](bw_index.gif)

|

![[Next]](bw_next.gif)

|

![[Last]](bw_last.gif)

|

|

|

Benvenuto Cellini - If you haven't read his autobiography, you should. It's a HOOT! Cellini was born in Florence, where his family had been landowners in the Val d'Ambra for three generations. His father, Giovanni Cellini, built and played musical instruments; he married Maria Lisabetta Granacci, and eighteen years elapsed before they had any progeny. Benvenuto (meaning "Welcome") was the third child. The father destined him for the same profession as himself, and endeavoured to thwart his inclination for design and metal work. When he had reached the age of fifteen, his father reluctantly agreed to his apprenticeship to a goldsmith, Antonio di Sandro, nicknamed Marcone. He had already attracted some notice in his native place, when, being implicated in a fray with some of his companions, he was banished for six months to Siena, where he worked for Francesco Castoro (Fracastoro), a goldsmith; from thence he removed to Bologna, where he became a more accomplished flute-player and made progress in the goldsmith's art. After visiting Pisa, and after twice resettling for a while in Florence (where he was visited by the sculptor Torrigiano, he decamped to Rome, aged nineteen. His first attempt at his craft here was a silver casket, followed by some silver candlesticks, and later by a vase for the bishop of Salamanca, which introduced him to the favourable notice of Pope Clement VII; likewise at a later date one of his celebrated works, the gold medallion of "Leda and the Swan" — the head and torso of Leda cut in hard stone — executed for the Gonfaloniere Gabbriello Cesarino, which is now in the Vienna museum; he also reverted to music, practised flute-playing, and was appointed one of the pope's court-musicians. In the attack upon Rome by the Constable de Bourbon, which occurred immediately after, the bravery and address of Cellini proved of signal service to the pontiff; if we may believe his own accounts, his was the very hand which shot the Bourbon dead, and he afterwards killed Philibert, Prince of Orange. His exploits paved the way for a reconciliation with the Florentine magistrates, and he return shortly to his native place. Here he assiduously devoted himself to the execution of medals, the most famous of which (executed a short while later) are "Hercules and the Nemean Lion", in gold repoussé work, and "Atlas supporting the Sphere", in chased gold, the latter eventually falling into the possession of Francis I. From Florence he went to the court of the duke of Mantua, and then again to Florence and to Rome, where he was employed not only in the working of jewelry, but also in the execution of dies for private medals and for the papal mint. Here in 1529 he killed his brother's murderer; and soon had to flee to Naples to shelter himself from the consequences of an affray with a notary, Ser Benedetto, whom he wounded. Through the influence of several of the cardinals he obtained a pardon; and on the elevation of Pope Paul III to the pontifical throne he was reinstated in his former position of favour, notwithstanding a fresh homicide of a goldsmith which he had committed more by accident than of malice prepense in the interregnum. Once more the plots of Pierluigi Farnese, a natural son of Paul III, led to his retreat from Rome to Florence and Venice, and once more he was restored with greater honour than before. On returning from a visit to the court of Francis I, being now aged thirty-seven, he was imprisoned on a charge (apparently false) of having embezzled during the war the gems of the pontifical tiara; he remained some while confined in the Castel Sant'Angelo, escaped, was recaptured, and treated with great severity, and was in daily expectation of death on the scaffold. At last, however, he was released at the intercession of Pierluigi's wife, and more especially of the Cardinal d'Este of Ferrara, to whom he presented a splendid cup. For a while, he worked at the court of Francis I, at Fontainebleau and Paris; but he considered the duchesse d'Étampes to be set against him, and the intrigues of the king's favourites, whom he would not stoop to conciliate and could not venture to silence by the sword, as he had silenced his enemies in Rome, led him, after about five years of laborious and sumptuous work, and of continually-recurring jealousies and violences, to retire in 1545 in disgust to Florence, where he employed his time in works of art, and exasperated his temper in rivalries with the uneasy-natured sculptor Baccio Bandinelli. The first collision between the two had occurred several years before when Pope Clement VII commissioned Cellini to mint his coinage. Now, in an altercation before Duke Cosimo, Bandinelli insultingly stigmatized Benvenuto as guilty of gross immorality, calling out to him Sta cheto, soddomitaccio! (Shut up, you filthy sodomite!); in his autobiography Cellini recalls repelling rather than denying the charge, claiming to be unworthy of such a divine and royal diversion. Certainly his art, often celebratory of the young male form, is a testimonial to his appreciation of that beauty. His biography omits the four charges against him of sodomy: 1) At the age of 23 with a boy named Domenico di ser Giuliano da Ripa, an accusation was settled with a small fine (perhaps thanks to his youth at the time). 2) An accusation in Paris, which he braved out in court. 3) In Florence in 1548, he was accused by a certain Margherita of familiarities with her son, Vincenzo. Perhaps this was a private quarrel, one from which he simply fled, and undeserving of attention. 4) Finally, in 1556, his apprentice Fernando, after being fired for an altercation, accused his mentor of: (as the indictment read) Cinque anni ha tenuto per suo ragazzo Fernando di Giovanni di Montepulciano, giovanetto con el quale ha usato carnalmente moltissime volte col nefando vitio della soddomia, tenendolo in letto come sua moglie (For five years he kept as his boy Fernando di Giovanni di Montepulciano, a youth whom he used carnally in the abject vice of sodomy numerous instances, keeping him in his bed as a wife.) This time the penalty was a hefty fifty golden scudi fine, and four years of prison, remitted to four years of house arrest thanks to the intercession of the Medicis. It is notable that his references to his boy models (and possibly lovers) are more tender and affectionate than his references to women. In his sculpture, the male is always more convincingly modelled than the female - his Venus of Fontainebleau, while notable, is unconvincing as a representation of the realistic female body. During the war with Siena, Cellini was appointed to strengthen the defences of his native city, and, though rather shabbily treated by his ducal patrons, he continued to gain the admiration of his fellow-citizens by the magnificent works which he produced. He died in Florence in 1571, unmarried, and leaving no posterity, and was buried with great pomp in the church of the Annunziata. He had supported in Florence a widowed sister and her six daughters. Not less characteristic of its splendidly gifted and barbarically untameable author are the autobiographical memoirs which he composed, beginning them in Florence in 1558 — a production of the utmost energy, directness and racy animation, setting forth one of the most singular careers in all the annals of fine art. His amours and hatreds, his passions and delights, his love of the sumptuous and the exquisite in art, his self-applause and self-assertion, running now and again into extravagances which it is impossible to credit, and difficult to set down as strictly conscious falsehoods, make this one of the most singular and fascinating books in existence. Here we read, not only of the strange and varied adventures of which we have presented a hasty sketch, but of the devout complacency with which Cellini could contemplate a satisfactorily achieved homicide; of the legion of devils which he and a conjuror evoked in the Colosseum, after one of his not innumerous mistresses had been spirited away from him by her mother; of the marvellous halo of light which he found surrounding his head at dawn and twilight after his Roman imprisonment, and his supernatural visions and angelic protection during that adversity; and of his being poisoned on several occasions. If he is unmeasured in abusing some people, he is also unlimited in praising others. The autobiography has been translated into English by Thomas Roscoe, by John Addington Symonds, and by A. Macdonald. It has been considered and published as a classic, and commonly regarded as one of the most colourful autobiographies (certainly the most important autobiography from the Renaissance). Cellini also wrote treatises on the goldsmith's art, on sculpture, and on design (translated by C. R. Ashbee, 1899). The life of Cellini also inspired the popular French author Alexandre Dumas. Dumas, an author of numerous historical novels wrote Ascanio, which was based on Cellini's life. The novel focuses on several years during Cellini's stay in France, working for Francis. The book is also centred around Ascanio, an apprentice of Cellini. The famous scheming, plot twists and intrigue that made Dumas famous feature in the novel, in this case involving, Cellini, the duchesse d'Etampes and other members of the court. Cellini is portrayed as a passionate and troubled man, plagued by the inconsistencies of life under the "patronage" of a false and somewhat cynical court. In addition to the opera by Berlioz, Cellini was also the subject of a Broadway musical, THE FIREBRAND OF FLORENCE, by Ira Gershwin and Kurt Weill, which featured Lotte Lenya (Mrs. Weill) as one of the sculptor's royal conquests. The show, unfortunately, was not a hit, and only ran for a month on Broadway, although some of its songs are periodically revived. It marked the last major collaboration between Weill and Gershwin. [Wikipedia] |

![[First]](bw_first.gif)

|

![[Prev]](bw_prev.gif)

|

![[Index]](bw_index.gif)

|

![[Next]](bw_next.gif)

|

![[Last]](bw_last.gif)

|