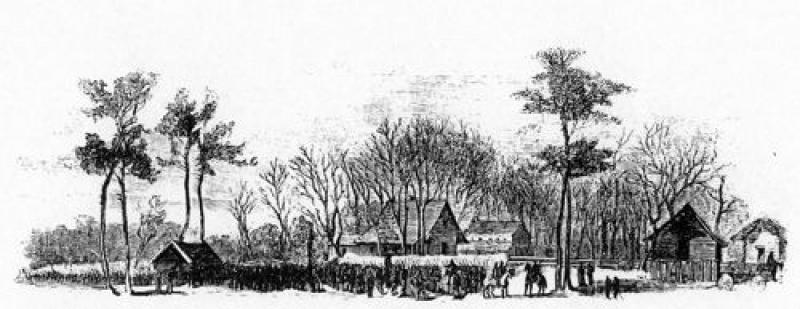

shows Union forces briefly occupying the Barber plantation during the Civil War.

by Laura Knight

~~~

|

The illustration is from the March 12, 1864 edition of Harper’s Weekly shows Union forces briefly occupying the Barber plantation during the Civil War. |

With Orlando’s present notoriety as the world’s favorite vacation destination, its history is often overlooked. This is unfortunate, because many would be surprised to discover “The City Beautiful” was once a rough and tumble frontier cow town. In fact, Orlando had a surly reputation worthy of any of its counterparts on the western frontier.

The U.S. Civil War did not ravage Florida to the extent it had her sister Confederate states; nevertheless, she joined them in suffering the humiliation of military occupation and the abject poverty that followed. Her salvation, it seemed, would be the massive herds of cattle that ranged her expansive prairies.

With the lifting of the Federal naval blockade, Florida’s cattlemen were free to establish a lucrative trade relationship with beef-hungry Cuba. A herd owner who could deliver his cattle to Cuban buyers in St. Augustine, Tampa, and other ports, could easily sell them for “hard money.” Soon, Spanish currency became more abundant than U.S. dollars.

The theft of this “hard money” was rare, but cattle rustling became a major problem—as did vigilante justice. Vigilantism prevailed because convictions on rustling charges were practically non-existent. It seems that people were unwilling to convict their neighbors of a crime they frequently committed themselves!

Lawlessness was rampant. The streets of Orlando were witness to brawls and random gunfire. Respectable citizens did not leave their homes after sundown, locking their doors against the nightly mayhem. It was these conditions that sparked a feud between Central Florida’s two most powerful families—the Barbers and the Mizells.

Two brothers named Moses and William Barber came to Northern Florida from Georgia in 1833, and settled near the present town of MacClenny. Though Indians killed William in 1841, the barbers thrived and built one of the largest cattle empires in the state. The 1860 Federal Census listed Moses as the owner of $21,400 worth of land and $116,180 of other property—including 100 slaves.

The Civil War nearly brought the Barber empire to its knees. Federal forces seized the family’s cattle to feed their invading armies, and seized their slaves as contraband. The ultimate blow came with the death of Moses’ son Isaiah at the battle of Gettysburg in 1863. This prompted the barbers to leave their home of 30 years and move to their more remote properties south of present-day Orlando, where they established a new ranch near Kenansville.

Three brothers named William, Luke, and David Moselle fled religious persecution in their native France to settle on the eastern shore of North Carolina prior to the American Revolution. Luke’s descendants later removed to Alabama, William’s to South Georgia, and David’s to Florida.

Editorial Note: The above statement is now known to be incorrect and derived from a long prevailing, but false, family myth. Luke Mizell was found in Surry County VA as early as 1635 and his sons, Luke JR and Lawrence also appeared in records from that time. His son, Lawrence, can be tracked from Surry VA to North Carolina to GA easily via now available records. The owner of this website has found burial records for William Mesles and Ellinor Mesles in the St Bride's Fleet Street, London, Parish Registry, 1620 and 1633 respectively.

A grandson of the original David, bearing the Anglicized name of David MIZELL, settled near present-day lake city in the 1830’s. It was there that Indians attacked his family in 1838, killing two loved-ones.

Editorial Note: The line runs: William Mesles & Ellinor, (d.1620, 1633 England) to Luke Mesles/Mizel (1614-1669 Surry VA) m. Deborah Lawrence, to Lawrence Mizell (1651-1694 NC) m. Bethinia (1654-1717) to Luke Mizell III (1683-1758 NC) m. Sarah Charlton (1685-1745) to Luke Mizell IV (1709 - ? NC) m Sarah Smithwick (1716-1786) to Charlton Mizell (1740-1819) m. Elizabeth Everett (1744-1815) to David Mizell (1770-1845) m. Nancy Evans. This latter David was the father of Nancy Mizell who married John Underwood Tippens, both of whom were killed by Indians.

David Mizell, Jr., enlisted in the ensuing war against the Indians and was stationed at Fort Christmas. He enjoyed his stay in Central Florida so much he convinced several of his kinfolk to settle in and around Orlando. Four of his sons fought in the Confederate Army during the Civil War: Thomas and Joshua, who were both killed in action; John, who rose to the rank of captain; and David, who saw little action as he was ill for most of his enlistment.

Despite his career as a Confederate officer, Captain John Mizell was somehow able to gain favor with Florida’s Reconstruction government after the war. He was appointed a judge and persuaded the governor to appoint his brother David as Sheriff of Orange County. These appointments made the Mizells the most powerful political family in the area. But, it also caused many of their neighbors to resent their cooperation with the oppressive carpetbaggers.

The government became particularly oppressive to the Barber family with the institution of a stiff tax on large herds. When the Mizells tried to enforce the government’s regulation of the cattle industry from their official positions of power, resentment that had been building against them began to boil over.

Barber family tradition holds that Andrew Jackson “Jack” Barber, a son of William Barber, was singled out by the Mizell brothers to serve as an example to his neighbors and kinfolk. They claim that Jack was continually harassed by warrants issued against him that did not even mention the date, place, or nature of his alleged offences. Even when he was cleared of charged brought against him, he was still made to pay court costs. Eventually, the Mizells did manage to convict Jack of some trumped-up charge and had him briefly incarcerated at the state prison at Chattahoochee.

Jack Barber’s nephew, Deed barber, also ran into trouble with the Mizells when his prize heifer “Taterpeelin” strayed onto the land of Morgan Mizell, a younger brother of Judge John Mizell and Sheriff David Mizell. In retrieving the heifer, he was intercepted by the sheriff who accused him of intending to steal some of Morgan’s herd. He wanted to indict the 14-year-old Deed, but diffused the situation for a time by choosing instead to slaughter the heifer and dividing the butchered carcass between the families.

The final straw for the barbers came when Sheriff David seized a large portion of Old Moses Barber’s Herd as a penalty for his refusal to pay the state cattle tax. Old Moses publicly threatened the sheriff: “The next time you enter my herd, you’ll come out feet first!”

The fall session of 1868 promised to be a tense face-off between the Barbers and the Mizells in the Orange County Court. Naturally, the Mizells had the upper hand given their official positions. But, the face-off was delayed—some say purposely.

Mary Mizell Speir, daughter of Sheriff David Mizell, had a nightmare and woke up in the middle of the night a few days before the county court was scheduled to convene. Looking through her bedroom window, she saw glinting lights dancing on the windowpanes. She jumped out of bed and saw that the courthouse was on fire. She sounded an alarm to awaken the sleeping citizens of Orlando.

The men of the town, some still in their nightshirts, battled the fire for some time but were unable to save the building. In fact, it appeared the fire would spread and destroy the entire downtown area. Sallie Mizell, another daughter of the sheriff, and her niece Anne Roberts risked their lives by running into the store belonging to her brother-in-law Edward W. Speir. They saved his ledgers as well as the post office receipts that he supervised.

Investigators later found empty bottles of turpentine and inflammable resin near the charred remains of the courthouse. All of the old county records were destroyed except one deed book that the county clerk had taken home to work on that night. It was an obvious case of arson but, while rumors abounded as to the identity of the arsonist, no witness to the crime came forward.

Three weeks after the fire, while spending a leisurely evening on their front porch, Mary and Ed Speir observed a stray dog wandering down the road. Mrs. Speir commented to her husband that, if he wanted to apprehend an arsonist, he should follow that dog for a while. A few hours later, Orlando’s jail burst into flames and the owner of the dog in question was widely suspected as the culprit. History does not record who this individual was, but he must have feared discovery from the scrutiny he received following Mrs. Speir’s prophecy. At any rate, there were no more fires in Orlando for quite some time.

|

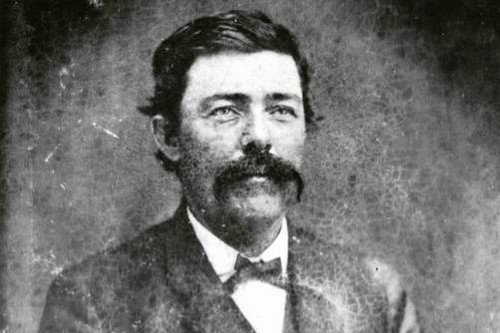

Orange County Sheriff, David Mizell |

Early in 1870, Robert Bullock filed a complaint against Old Moses Barber for an unpaid bill of sale on a number of cattle. Judge John Mizell issued a warrant for Moses’ arrest and sent his brother Sheriff David Mizell to bring him to Orlando for a trial. David took his 12-year-old son Billy and his brother Morgan and headed south to the Barber Ranch.

The lawmen stopped on the evening of February 21st to water their horses at Bull Creek, a short ride from their destination. Suddenly, they were sprayed with gunfire. Billy and Morgan were unscathed by the ambush, but the sheriff was mortally wounded.

Morgan instructed his nephew Billy to tend to his dying father, and then galloped back to Orlando for help. On his ride, he encountered a man named George Sullivan who rushed to join Billy at Bull Creek. The boy later recalled that his father regained consciousness shortly before he died and asked that no one seek revenge for his murder. Sadly, no one honored this last request.

|

| Angeline Mizell, the widow of slain Orange County Sheriff David Mizell with (L to R) standing: John Thomas Mizell, Lulu Amanda, Joshua and Della; seated: Sarah Ann, Angeline and Mollie. (Hist. Soc. of Central FL Inc.) |

Judge John Mizell did not heed his brother’s dying words. He immediately organized a posse of twenty local men, ordered them to bring the Barbers to justice, and instructed them to take no prisoners. He appointed David B. Stewart to replace his brother as Sheriff and lead the posse south to fulfill its mission.

The posse’s first act was to arrest Needham Yates (an uncle of Jack Barber) and his sons William and Needham, Jr., because they were suspected of participating in the ambush.

The next suspect the posse encountered was Old Moses Barber’s son Isaac. Judge Mizell ordered his men to tie Isaac to the nearest tree. Then, all twenty men simultaneously emptied their guns into the bound man so that no one individual could be accused of his murder.

News of this heinous act quickly spread through the neighborhood so that Old Moses, Jack, and Moses Barber, Jr., were able to flee their ranch before the posse arrived. Isaac’s enraged widow, Harriet Geiger Barber, met the judge and his men instead. It is said that she cursed the lawmen with such foul language that they hurriedly seized her cattle and sped away, anxious to escape her tirade. For many years, she would keep the bullet-torn coat that her husband had worn when murdered—and her hatred for the Mizells would last the rest of her life.

Judge Mizell returned to Orlando with the Barber herd and most of his posse. A few of his men, though, chose to pursue Old Moses, Jack, and Moses, Jr. They almost succeeded in capturing the trio, too. But, their horses became mired in what was then known as shingle creek. Ultimately, they only succeeded in capturing Moses, Jr., whose horse also bogged down in the mud. It was this incident that earned the stream its current name: Boggy Creek.

According to three members of the posse — Jack Evans, Joe Moody, and Bill Duffield — the lawmen made camp south of lake Conway. Fearing that Moses Barber, Jr., might attempt to escape during the night, they shackled him in irons. When they awoke the next morning, they claimed Barber had done exactly as they suspected he might. They tracked his escape route directly to the shores of the lake where his drowned body was later found.

According to the Barber family, the lawmen behaved in a more sinister manner. Their version states the posse heeded Judge John Mizell’s order not to take any prisoners, placed a ploughshare around Moses’ neck, put him in a croaker sack, and threw him into the lake. Somehow, they claim, he was able to free himself from the sack and ploughshare and tried to swim to safety. But, the posse opened fire on the doomed man and he never made it to the shore alive.

Whichever version is correct, both agree that Moses Barber, Jr., did drown in Lake Conway. A Barber descendant recently wrote that his body was found near a pond on South Ferncreek Road, which had been part of Lake Conway at the time of the feud. This site was later reported to be haunted by the drowned man’s ghost, and was a source of much terror for the local youngsters.

The hasty departure of the barbers did not bring peace to the area. A flood saturated the region’s farmland and destroyed the farmers’ crops. They turned to cattle as the only viable source of income, which resulted in even more rustling, murder, and lawlessness.

In the single year of 1871, there were forty-one reported murders in Orange County. The fact that only ten cases were ever brought to court and NO guilty verdicts returned speaks for the ineffectiveness of the Reconstruction Era justice system in dealing with crime. Peace was finally achieved when private citizens like Philip Leonardy of St. Augustine realized the lawlessness was cutting into the industry’s profitability and worked tirelessly to mediate disputes.

Feelings between the feuding families continued to simmer below the surface for many years. In fact, the feud did not really come to an end for at least three generations when William J. Barber—a grandson of the murdered Isaac Barber—and Mary Ida Mizell—a descendant of Judge John Mizell—were married. Today, though verbal barbs might still be tossed about, they are generally good-humored in nature.

· Isaac Barber, 35, white male, married, born in Georgia, shot in March.

· Moses Barber, 37, white male, married, born in Georgia, Farmer, drowned in March.

· William Bronson, 37, white male, married, farmer, born in South Carolina, shot in March.

· David Mizell, 40, white male, married, born in Georgia, Sheriff, murdered in March.

· Needham Yates, 52, white male, married, born in Georgia, Farmer, shot in March.

· William Yates, 32, white male, married, born in Georgia, Farmer, shot in March.

· Henry W. Barber (3 Jan 1863 – 8 Nov 1901)

· Infant son of Dan and Viola Barber

· Warren Barber (1890-1973) and Elizabeth (1896 - ?)

· Edmund Dennis Barber (17 Feb 1920 – 30 Dec 1982)

· Joseph Barber (27 Sept 1860 – 5 June 1893)

· Isaac Barber (29 July 1835 – 20 March 1870), killed during the feud

· Infant son of John and Della Barber, 20 Feb 1919

For Futher Reading:

· “Cattle Feud Slaughtered Mizells, Barbers during Reconstruction,” by Mark Andrews, The Orlando Sentinel, Sunday, March 29, 1992, Page K-6.

· Orlando: A Centennial History, by Eve Bacon, The Mickler House Publishers, Chuluota, Florida, 1975.

· Pine Castle: A Walk Down Memory Lane, by Ruth Barber Linton, Book Crafters, Chelsea, Michigan, 1993.

· Pioneers of Wiregrass Georgia, by Huxford Folks ( A series of genealogical compilations covering the counties of Irwin, Appling, Wayne, Camden, and Glynn).

· Orlando in the Long, long, ago . . . and now, by Kena Fries, Florida Press, Orlando, 1938.

· Florida’s Frontier: The Way Hit Wuz, by Mary Ida Bass Shearhart, Magnolia Press, Gainesville, Georgia, 1992. Write her at: 2850 Boggy Creek Road, Kissimmee, FL 34744.

Shared from the True Florida Cracker facebook group. assembled by Susan Arline Williams