by Laura Knight

So, you are a Knight or connected to a Knight in some way. Maybe you want a family pedigree or a Coat of Arms or a connection to royalty; or maybe you are interested in history at the personal level? Maybe you have heard about, or participated in Family Constellations Therapy and want to see if who you are is the result of who your ancestors were. Maybe you are a member of the LDS church and want to "seal" your ancestors? Maybe you have just caught the Genealogy Bug?

You’ve probably gone to the internet to do some research, and at first it was pretty exciting finding this connection and that one; but then, after awhile, you realized that some of these people, places, and times just don’t fit quite right, the records aren’t there, or the records contradict the claims; or you have seen that there are egregious conflicts in claims made by different alleged family trees. Perhaps you have seen that people are in some trees who are older than their parents. One of my favorites was seeing a birth record claimed for an individual in Virginia Colony, and a baptismal record claimed where the baptism took place in London on the same day. I hate to have to inform the person who created that aberration that the Concorde was not yet in service in 1627.

It seems that everyone is sure that the progenitor of the Southern Knights, the Virginia Knights, is a certain Capt. Peter Knight, and many amateur genealogists are content to leave it at that; but the truth is, the genealogies are not at all secure for a variety of reasons, the main one being certain gaps in the records which allowed – even demanded – to be filled in with something, and those theorized connections and stories then came to be seen as hard facts though there was no support for them whatsoever.

When more modern methods of genealogy came along, and workers in the field began to search for, uncover, and transcribe, and publish the actual records, most Knights didn’t really get onboard and take advantage of this wealth of material because they were generally certain that it had already been done and dusted. There was a good story, names and dates that fit more or less, why bother to dig any deeper?

The main problem with Knight genealogy is actually Capt. Peter himself; he was a larger than life figure who made something of a splash in Virginia for about 50 years and then just disappeared from the stage of history. For some reason, unlike other families, the Knights did not continue to make so public a spectacle of themselves that they were written about in the histories and diaries produced through Revolutionary times. There were Knights, in records here and there that emerged from the Dark Age of the Revolution with no clear indications of their antecedants. People started moving, people started showing up here and there, but there were no firm connections for many of them and in particular, several John Knights who showed up in South Carolina and Georgia and nobody can figure out where they came from and who to connect them to upline. You have to remember that the American Revolution was a protracted conflict and many records were destroyed or simply never created at all.

Like most Southern Knights, I can go up my family tree on the Knight line to almost the Revolution with great certainty, but I can’t go past that barrier with any documentary proof, and for nearly everyone, it is due to that breakdown in records and the fact that so many people in the same familes gave their children the same names; if you don’t have a will, some deeds, birth certificates or other documents stating who the parents are (Bible records are often good unless they are faked, which happens), you are pretty much up the creek.

Lucian Lamar Knight author of Genealogy of the Knight, Walton, Woodson, Lamar, Daniel, Bennig, Cobb, Jackson, Grant and Other Georgia Families, is largely responsible for the current sad state of Knight genealogy; I'm sure he would be most dismayed to realize that. He was born in 1868 and, at that time, there were still people living who recalled their grandparents and perhaps held some information about great-grandparents. He was a lawyer, a journalist/editor, a Presbyterian minister, and then a journalist again. Through all these activities, he was mostly devoted to studying history, mainly history as it pertained to his own origins, it seems. He wrote and published two volumes of Reminiscences of Famous Georgians (1907 and 1908). Beginning in 1911, he edited the “Library of Southern Literature” with Joel Chandler Harris. In 1913, Lucian was appointed compiler of Georgia state records and began work on volumes 22-26 of Colonial Records, another volume entitled Georgia’s Landmarks, Memorials, and Legends, and a six volume history of Georgia. We can thank Lucian for his active lobbying for the preservation of records; when he retired in 1925, he left a new department with proper storage for state records in Georgia. You can read a short, but relatively complete bio HERE .

Because of his fine education and literary accomplishments, Lucian’s short histories of the Knights and the related Woodsons has been taken as gospel for about a hundred years. However, in the time since he researched and wrote, a great deal more records have been made available by the dedicated toil of archivists and genealogical researchers, the often unsung heroes of what might be considered a branch of antiquarian historical research; as the great classicist and historian of Rome, Ronald Syme demonstrated, sometimes families and their connections can reveal a lot about how and why bigger things in history that catch the eye actually happen.

The bottom line is, though, that Lucian’s work is now not just superseded, it is almost entirely irrelevant since much of it is just plain wrong. Notice that I said “much”, not “all." He's pretty good when he is working closer to his own time.

Lucian Knight begins his story of the Knight family by a pointed mention of Sir Thomas Knight of Chawton Manor and then transitions smoothly to the earliest Knight in Virginia, Peter, as though it must be accepted that the latter descended from the former. He suggests that Peter Knight may have come to Virginia as early as 1607, and by 1638 was a “long established resident at Jamestown, where he was then a merchant, operating an extensive business chiefly on the ocean.” We are going to learn, from the records assembled in this volume, that it didn’t happen exactly that way at all.

Lucian’s romanticism is on full display when he writes about the fact that many indentured servants who were sent to the Colony of Virginia just happened to be collected from the English prisons:

Some of the gentlest spirits in England were at this time thrown into prison wards and to realize what wrongs were suffered by innocent offenders, whose only crime was a paltry debt, one needs only to read Little Dorrit, a Child of the Marshalsea, by the great novelist, Charles Dickens. If I remember correctly his father was for years an inmate of the Fleet or of some other or equally repugnant place of detention. (Knight, p. 3)

It is certainly true that Dickens exposed the moral failings of the English, but Lucian’s agenda is to give a good cover story for why there were some Knights – clearly “some of the gentlest spirits in England” – who happened to appear in the lists of those used as headrights in Virginia, i.e. must have been indentured servants. As we will learn in the records section, the whole headrights system was not exactly as it has been portrayed by most genealogists or historians even to the present day. Lucian is also writing apology for Peter Knight who clearly used a lot of people as headrights to acquire some good sized tracts of land. And this may be what was sticking in Lucian’s craw; he writes:

Peter Knight was not only a merchant but a planter, and his [land] grants were scattered over several counties in the tide-water region. Indeed the frequency with which his name occurs in the colonial records is proof conclusive that no man of his day was more active in colonial affairs and he must have accumulated a fortune baronial in its proportions. (Knight, p. 4, emphasis, mine.)

Lucian completely misunderstood what he was reading in the colonial records he mentions. There were actually at least two Peter Knights (possibly 3), and the activity of the two of them might indeed make it seem that one individual was some sort of hyper-active land baron, but a detailed examination proves that this isn’t necessarily so, at least not exactly in those terms. Lucian then notes:

But every effort to locate his grave has failed, and no other monument can be found to him, save those of the immigration and court house records from which we have quoted. (Knight, p. 4)

The main problem with this is that Lucian didn’t actually quote much in the way of “immigration and court-house records”. But it is quite true that, despite the impressive activity in Colonial Virginia of the (at least) two Peter Knights, and the far-reaching impact they had on many other families down through the generations, we have no idea where either of them were buried, and the few references to them after death (both of them), do not give the impression of any great regard for them by their immediate or near contemporaries. They were merchants and planters, after all, and apparently were not seeking to make a big splash or mark on the world in which they lived; it was all business.

Lucian then makes another big error when he writes:

…the famous buccaneer by the name of Blackbeard who carried on his forbidden trade among the rocks of the North Carolina coast is known to have been a Knight and according to popular tradition was a kinsman of the Virginia merchant. (Knight, p. 4)

Now, I do NOT know where the heck Lucian came up with that one, but it is not only not true from where I sit, it was not true from where Lucian sat, and the records regarding the relationship between Tobias Knight, a colonial official of North Carolina, and the notorious Blackbeard whose real name was Edward Thache, were certainly available to Lucian had he made the effort to search. You can get the straight story on Tobias (no apparent relation to Peter Knight) HERE. For the most up-to-date research on Blackbeard, read the genealogical research of maritime historian, Baylus C. Brooks: Quest for Blackbeard. You can find it on amazon.com. Lucian appears to have thought that Tobias Knight and Blackbeard were one and the same person and that Tobias was related to the Peter Knights, neither of which was true.

The biggest set of compound errors made by Lucian was when he wrote the following:

Some ten counties at least in tide-water Virginia contain the extensive tracts of land which belonged at one time to Captain Peter Knight and these admit of no doubt concerning the great wealth or the immense business activities of this Knight of pioneer days, who must indeed have been a prince of merchants, even for those opulent days. His son, William, inherited much of his property, along with other children, though he has left fe memorials and not even his will can be found among the probate papers of the early colonial period. However, his grandson, John Knight Sr., appears in Sussex county where he left a will probated on the 7th day of February 1760, leaving behind him a large family to share his substantial bequests, including nine children to wit: William John, Joel, Edward, Peter, Richard, Sarah, Ann, Mary and Jordan. He also left a grandson, John, of whom special mention is made in his last will and testament. His wife was Elizabeth Jordan. Under the conditions of life in those days he was unable to write his name and in place of a signature made his mark. (Knight, p. 5)

Lucian then produces the will of this alleged grandson and this transcription stands as the first actual record he utilizes to back up his many claims for his version of the Knight family of Virginia.

I am actually astonished by the sleight of hand I have just witnessed. If you read his book, you will see that Lucian went from Thomas Knight of Chawton Manor, to Peter Knight (singular) of Virginia, to a William Knight, to John Knight of Sussex, to John Knight of Lunenburg, and deftly excuses the lack of literacy of John Knight of Sussex. He then makes a rather feeble attempt to explain why John Knight of Sussex didn’t appear to have any of the vast landholdings of his alleged grandfather, Peter Knight the wealthy land baron. He then passes on to the will of John Knight of Lunenburg, his wife Elizabeth Woodson, and a paean of praise of the Woodson family.

And so it goes. Don’t get me wrong, I am a born Knight and I would like it a lot for the fantasies of Lucian to be true; life would be so simple; Lucian researched things as best he could (perhaps, I’m not so sure anymore), wrote a nice summary of his work, and the rest of us can just attach ourselves to the magic tree and be content! The only problem is, when you work with the real material at hand, digging into the actual records and really reading and considering them, it just doesn’t work. The unfortunate fact is that the John Knight, son of John Knight of Sussex who left the will, ALSO left a will, and he is most definitely NOT John Knight of Lunenburg nor was he married to Elizabeth Woodson; he was married to Elizabeth Stokes, 1st, and a woman named Sarah 2nd. The records exist, and that one single fact completely demolishes Lucian’s lynchpin connection between the Knights of Sussex and John Knight of Lunenburg. And where he found the mythical William Knight, son of Peter, I have never been able to determine.

Genealogy by copying someone else’s family tree (you don’t know who created it and what their aims were!) is just not methodologically sound, especially if that tree is not supported by a raft of records that clearly make sense; someone else’s tree that lacks the records may give you a clue, but then it is up to you to search for the actual records that support the existence of the person and the claimed connection. Very often, what records are available will only allow you to infer the connection, and sometimes, that sort of evidence is compelling enough to plug somebody into the slot. And using someone else's tree, or LDS claims based on those trees, is just not reliable.

On the other hand, where other people’s trees are most useful is when they are dealing with their own specific branch and more or less immediate family back maybe 3 or 4 generations. If someone in your family – say your great-grandmother – wrote down the names of her mother’s parents and siblings, and you are told that one of them went off and lost touch with the rest of the family and nobody ever knew what happened to him or her, and then you find some other family you know nothing about, and they just happen to have that lost individual as their ancestor, and for them, he is also only a few generations back and is well documented, you are justified in making the link-up. That’s the beauty of networking family research. People really can find long lost connections!

This has actually happened for me: finding the families of lost siblings of great grandparents and even great-great-grandparents. Making contact with those descendants has helped me to fill in a lot of blanks going back 5 or 6 generations! Here I will note that you should never neglect a collateral line because it isn’t your direct line because you never know what information will come to you from going that direction!

But when dealing with generations much further back on the family tree, things get a little tougher and the terrible problem of brick walls that will never come tumbling down exists as a hard reality. And you can’t just wish it away and connect to somebody who isn’t actually a real connection because there is nobody else around who will do! Well, you can do it if you want a Fake Family Tree; I don't know about you, but I want to know the truth.

There is a handy little book entitled Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS) by genealogist Christine Rose (the Rose family is an old one of Virginia); if you are working on your family history, you really should read this book. She explains the five points of the GPS as follows:

Let me rant a moment about the incredible frustration I have felt when viewing the work of many online amateur genealogists who quite simply do not have the courtesy to provide clear, accurate citations for their material. Let me also add that ancestry.com doesn’t make it easy to add quoted material and citations; the process is so convoluted that I just gave up and that’s why I’m putting it all online here.

Now, what are sources? Rose tell us that there are three kinds: Original, Derivative, Authored.

[Authors] may have used only limited sources, misinterpreted some documents, or even misread them.

[I]mage copies, regardless of date or creation, hold more weight than other types of derivatives such as abstracts, transcriptions, and other “non-images” because the latter are subject to errors introduced by human interpretation.

[T]he “farther away” a derivative is from the original record, the more chance of error.

The information is primary if it was made orally or in writing (or even pictorially) by someone in a position to know firsthand (such as an eyewitness or a participant) and recorded in a timely manner while memory is fresh. The informant may have provided faulty information, but nonetheless the information is considered primary information. “Primary” does not ensure accuracy.

[A] 1700 birth entry in a Bible published in 1875 could not have been inscribed by someone with firsthand knowledge of the 1700 event… if the writer had the original birth record in front of them, and entered it from that source .. it would now be a derivative source, but still primary information. If evidence is primary information it remains primary even though it may be from a derivative source. (Rose 2014, p. 5-9 snips in order, emphases mine.)

The last item in bold is why it is so, so, so important for each and every bit of data to be accompanied by a source citation of sufficient exactness that anyone can go and find it. You may be giving primary information but if you do not describe it, it becomes useless for anyone else; it becomes, essentially “authored information”! If you provide information from your family Bible, inscribed as the events occurred by the hand of your great grandmother, it is useless to anyone else if they do not know who wrote it, when it was written, where it was written, and the present location of the Bible in question. And even better is to accompany that information with a good, clear, photographic image of the Bible entries. The same is true for anything else you find and share with others; be courteous and cite the source accurately and completely!

In general, it is necessary to know who provided the information and whether or not they are reliable! It is also necessary to know why the record was created. As Rose notes, a will is created to distribute real property and goods and is legally recorded. An application for a government pension can be a whole lot of fudging because the “why” is to qualify to get the money from the government. A family history may be written by a descendant and claimed to have been told to him by an “old timer” who was there, and be completely concocted for various purposes, usually to make social connections, or cover up social liabilities. We have already seen what Lucian Lama Knight wrote, and we will encounter a few egregious cases of “just making stuff up” because of a particular agenda.

Let me again strongly urge the amateur genealogist to please read Genealogical Proof Standard by Christine Rose and do the job well! After all, you do want to know the truth about your ancestors, don’t you? You do want to pass the truth on to your children, don’t you? What’s the point of claiming to be descended from William the Conqueror if it isn’t true? Well, sure, you can make social hay with that, but his blood isn’t in your veins and you are living a lie. Plus, after reading the histories of some noble dudes and dudesses, most of them were people I wouldn’t want at my dinner table much less associating with my children so why the heck would I want them in my family tree if it wasn't true?

In the earliest days of working on my genealogy, I was happy enough to work from Giles and Abel Knight who was said to be a close companion of William Penn and they were all Quakers. This tree was interesting and went all the way back to a Willielmo Knyght b. 1325 in Worcester, England. How cool is that?!

However, it bothered me that there were no accompanying source citations for the most ancient parts of this tree, and, upon reading it carefully, I came across a huge, glaring anomaly. The line went like this, top down: 1Willielmo, 2Ralph, 3William, 4William, 5John, 6John, 7George, 8John, 9John, 10Edward, 11Giles, 12Abel, 13John, 14John. And then, under 12Abel the following notes:

From: Knyght after Knyght: John Knight and his sister Ann came to America with William Penn arriving on the "Society" in Aughst, 1682. Their brothers Abel and Giles came on the "Welcome" which left England August 30, 1682 and arrived at New Castle on the "Delaware" the second week of November. Giles was accompanied on the voyage by his wife Mary English and son, Joseph Knight. Brothers Abel and John were not listed as supporters (of the friends of Byberry). Perhaps it was this religious rift which prompted Abel Knight to relocate to North Carolina.

And then, under 13John there was this:

Children of JOHN KNIGHT are:

ii. EDWARD KNIGHT.

iii. WILLIAM KNIGHT, b. 1690, Bertie County, North Carolina; d. December 03, 1751, Bertie County, North Carolina; m. MARTHA.

This was accompanied by the following “citations”: (I’m redacting the addresses of the providers of the alleged information for privacy reasons):

Sources:

And then, under 14John there was this blockbuster:

Notes for JOHN KNIGHT , XIII: He lived in Sussex, Sussex Co, VA.He was either a grandson or great-grandson of the pioneer immigrant, Captain Peter Knight. (History And Family Tree of John Knight, R.S.) Will date d 17 Feb 1760, probated 18 Feb 1762 (Sussex Co., VA Will Book A, p. 229). (Carolyn Tamblyn)

Leaving aside the fact that the information about the will of Capt. Peter being wrong, the compiler of this tree appeared to be oblivious to the fact that s/he had just given 14John a father, grandfather and great-grandfather, i.e. 10Edward, 11Giles, 12Abel, which completely excluded any such person as a Peter Knight of Virginia. But it got worse. The next item, the 15th generation was… drum roll… Peter Knight III! It boggles the mind!

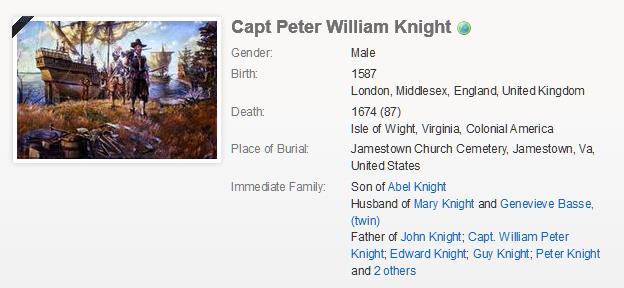

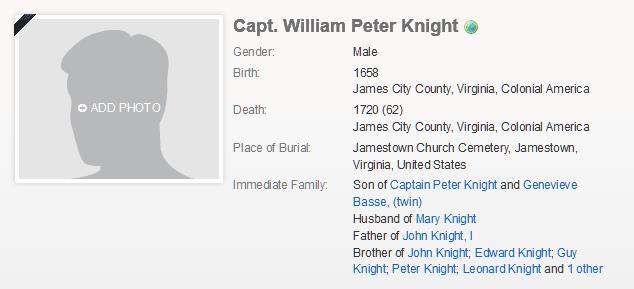

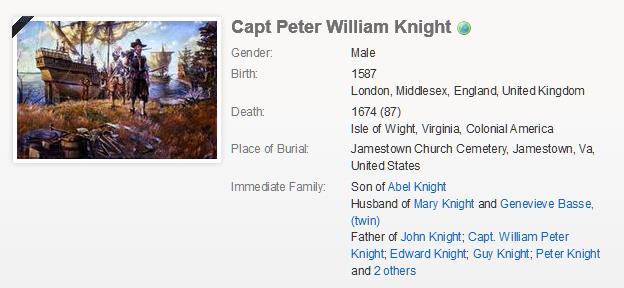

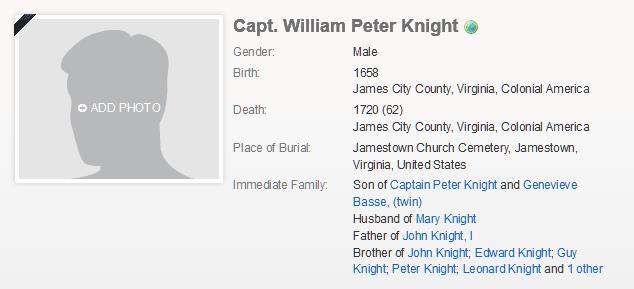

Believe it or not, this nonsense still prevails on the internet. Just yesterday, 2019 Feb 1, I took two screenshots of profiles of Peter Knight of Virginia on the Geni website:

|

|

Words fail me.

In any event, way back when, realizing that something was seriously wrong with this picture, I started searching out information about this Peter Knight of Virginia. I soon realized that there was more than one Knight family progenitor in the early colonies and it appeared that the Peter Knight line was quite distinct from the Giles/Abel Knight line, though they could be related much further back in England (which I still think may be the case though it will take DNA to sort it out.)

Apparently the folks who were working the Peter Knight line were a lot more savvy about the Virginia Knights and were, at least, digging into the VA records to a limited extent. However, even those lines were confused thanks to the misleading influence of Lucian Lamar Knight, though I didn't realize it at the time.

At this point, still being a complete amateur, I was happy to put my tree together based on what Lucian had written and with gaps filled in by some other creative souls with a few records. I was pleased to have Genevieve Basse as an ancestor and to be connected to all her alleged interesting antecedents. Peter, of course, had equally interesting ancestors. It was all a done deal; just fill it in and move on. After all, I did have other lines of Virginia pioneers in addition to Knights: Meadows, Collins, Mizell, Pearce, Colson, and all the families connected to them.

For quite a number of years I worked intermittently on the tree. I got serious enough at one point to purchase a microfiche reader and packets of microfilm so I could search records myself and I did make some remarkable discoveries that have since become part of the wider genealogical lore. But mostly I was concentrating on those other lines. As far as I could see, the Knight line had been taken care of. Obviously everyone has a lot of other lines. If you count back just 6 generations, you will have 128 5th great grandparents and that means 128 (usually) completely different family names and lines to research and explore. I can get about that far on most of my DNA contributors, and on some, I can go a lot further.

After some years went by, this current project - concentrating hard on the Knight family - began, as many projects do, as just a little side-job: I wanted to finalize the family tree so I could print it out as a supplement to illustrate the family photo album; you know, just get in the important people a few generations back, get some documentation to include so that the people come to life, and be done with it; quick and easy, take a week or two! I had been working from online sources quite a bit over the years and had purchased many CDs of records from various family tree organizations. At this point, in order to try to fill in a few weak areas, I decided to join ancestry.com, so that I could access and collect records for my project. At the same time, I began buying even more books of records that might have something pertaining to Knights and soon had acquired pretty much all the major sources. Instead of just looking in the index to find my target people, I found these compilations so interesting that I spent months reading them in their entirety; sometimes it was better than a novel! (I should mention that this was a period of time during which I was recovering from severe injuries that required immobilization so my idea of what was exciting was seriously altered!) I would read, insert tabs to be able to find the interesting records, and then later, when I was able to sit at my desk, began to type up my extracts in chronological order.

Basically, I undertook the huge project of gathering every single Knight record I could find, to attempt to figure out who was who and who really did what. Since historical research has occupied me for all of my adult life (ancient history is my speciality), I went about this in much the same way one does historical research: I undertook to find out as much about the society and the environment as I could so that I could place the individual people in their proper context. That meant, of course, a LOT of reading. In historical research, you have to read original texts if there are any available. It’s not enough to read a biography of Julius Caesar by some historian, early or modern, one needs to read all the texts of the time where primary evidence about Caesar was written down by his contemporaries close to the time of events and observations recorded. And in the case of Caesar, it has to be understood that those writing the texts did, indeed, have agendas and the dictum “Primary does not ensure accuracy” kept firmly in mind. Fortunately, with the kinds of records we will be dealing with here, politics is not much of an issue though it will rear its head from time to time.

When I started searching and compiling records, I began with Peter Knight and all other Knights in Virginia and worked forward; I wanted to find the links that filled in that gap of the Revolution if any such existed. I went through all the land records, court records, will collections, parish registers, diaries and compilations of various papers etc. If I read a single hint that there was a Knight in one or another county, I bought the compilations of records for that county. I followed the Knights all around Virginia and then to North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. I knew I needed enough of a scope covering those areas to differentiate between families, so I’ve cast the net pretty wide. I kept moving forward, hoping for a breakthrough, right up to the census of 1850. All of these records involving Knights are on this website (or will be uploaded as soon as possible).

The picture of the Knights that began to emerge from the records themselves was very, very different in many respects from that presented in online genealogies.

At a certain point, I decided that I needed to do DNA testing to try to help sort things out. My brother agreed, so I have the paternal DNA to work with too. With the DNA information available, I realized that I needed to go backward into England. Again using Capt. Peter Knight as the jumping off point, and that’s what I did: searching for and compiling records of Knights in England. It was then that some really startling discoveries were made that completely overturn most of the online Knight genealogies at that level. It was disconcerting, but understandable; before the internet and the intense interest in genealogy among ordinary people, the records simply were not available. And since people had already constructed their trees based on less comprehensive research, nobody felt inclined to upset the apple cart.

The bottom line is that I did a monstrous amount of reading and compiling. For example, if I found a family in a parish register, I read the entire register (if I could get it) because I wanted to know who my target people knew and what kind of people they were, as a group. When I read court records, I didn’t just aim for my target person, I read the entire collection because I wanted to know how the friends and neighbors were acting and interacting and who connected to who else. When I read land records, I read ALL of the compilation and if neighboring land owners were mentioned, I would follow up their activities to see if anything interesting was going on. If an abstract was particularly interesting or problematic, I would seek out the full transcription if I could get it; unfortunately, I am not in a position to physically go to hundreds of archive locations, just like most people, so I wasn’t always successful in finding full transcripts; but everything I have found, with citations of where the original is located, is (or will be) on this website.

In going about the search in this way, I did, indeed, find some crucial clues; I also learned a lot about “how things were done” so that I could better evaluate my own speculations about what might, or must, have happened. The end result was that I collected records of other families along the way, though not in the same, exhaustive way I was collecting Knight records; but enough to reveal many family and name affiliations that persisted through the generations. And so, I am including a selection of the records of other families in this collection when it sheds light on our Knights.

At one point, I created a database that correlated time and location by Colonial county. Every single Knight I could find was entered into their appropriate box according to the year and the location. This was a bit tricky because counties kept being divided and sub-divided, renamed, and so forth. At every point in that stage of the process, I had to keep one eye on the column header which named the county, and another on a list of county names and boundary changes. I ended up piling some county names together because it was clear that the person had not moved, just the name of where they lived changed. (This is part of what gave Lucian Lamar Knight the impression of Peter Knight’s "baronial" possessions which wasn’t exactly the case, added to the fact that he conflated two entirely different Peter Knights.) In any event, this little trick allowed me to see how families clustered and who belonged to whom and when they disappeared from one place, where they appeared next. It’s not perfect, and there are anomalies, but overall, it was a big help, and it could only have been done with as large a collection of records as I had amassed, which are presented on this website. I gave the English records the same database treatment, and this will be correlated to maps on this website in an interactive way so that you can see for yourself who was where and when. I will also see if I can just upload the database so that those who are skilled with such things can manipulate the sorting to see what else may be found.

The general results are that there appear to be four main groups:

1) The Peter-Leonard Knights, descended directly and clearly from Capt. Peter, and which descent can be pretty well followed; at least one of them went to South Carolina and others went in a more Westerly direction.

2) The Coleman-Woodson Knights whose descent is uncertain, but probably this John Knight of Lunenburg descended from one of three Knight brothers of Jamestown who married the daughter of a certain Mr. Anthony Coleman; it is not determinable from the records that this group are even related to either of the Peter Knights; these Knights went to Granville County NC, to South Carolina, and then to Georgia; (some of them, that is).

3) The Moore-Carter-Spier Knights that appear rather suddenly in Edgecombe County North Carolina which are apparently closely connected to the next group;

4) The Jordan-Eppes-Peter Knights that are found in Albemarle Parish, Surry/Sussex County VA, and then in Edgecombe County, North Carolina.

The first group have a clear connection backed up by records. The latter three certainly have records, wills, land, and such that force us to exclude the possibility that they can be amalgamated into single families; the problem is connecting them to parents and knowing from whom those parents descend. Leaving aside the Peter-Leonard Knights and just looking at the three primary families, all begun by a John Knight, is enough to give one a headache.

John Knight (1713-1772) of Lunenburg who married Elizabeth Woodson left a will naming his children and several of his children left wills that exclude them from certain family relationships that they have been assigned in error. Their NC stomping ground was Granville County and descendants showed up in SC and GA and elsewhere. They did not seem to favor the name “Peter”; they favored “Woodson” and “Coleman” and John (!) . However, they were associated with some Jordans because an Elizabeth Woodson (1751-1780) married a William Jordan (1750-1817) and produced a son, Woodson Jordan (1772).

John Knight (c. 1705-1769) who married Isabell Carter and died in Edgecombe County NC, left a will naming his children. His son, John (m. Ann pos Bell), also left a will naming children and cannot be conflated with John Knight of Lunenburg.

John Knight (1690-1762), who died in Sussex County VA and also left a will naming his children; he appears to have married 1st Elizabeth Jordan and 2nd Elizabeth Eppes leading to massive confusion. A close and careful study of the Albemarle Parish registry brings me to that conclusion as will be shown in the actual records; and if it is true, as I argue it is, it solves one of the big problems of Knight genealogy.

This family favored the name “Peter” along with Eppes and Jordan.

Lucian Lamar Knight appears to be definitely descended from the Woodson-Coleman Knights; it appears that about every Colonial family that survived the hardships of the early times, sent out settlers from Virginia to North Carolina/South Carolina, and Georgia. The GA to FL Knights appear to be descended from the Jordan-Eppes and Moore-Carter-Spier Knights (my branch) though others went to other places, as will be seen.

The most pressing problem about these three Johns and their families is: who were their parents? Obviously, since they were all born around the same time, 1690, 1705, 1713, they cannot have the same parents, and obviously, all three of them existed because the records exist! Also, their wills exclude descent from John 1690 to John 1713. And if there were three sets of parents for these three John Knights, who were they and who were the parents of the parents? Do they connect in some way to either of the Peter Knights? And if so, how? That is the gap we face and there are no records that I can see that close that gap, but we can make some intelligent inferences, as I will. I have also found some records in England that suggest origins, and it appears that DNA could solve the problem, at least in terms of knowing which branch a person really belongs to, though placeholders may still be needed to fill in the blank spaces cause by the loss of records.

Whatever solution I can give to the gap will only be an inference based on as many facts and bits of data I can assemble to support a link; what’s more, it appears inevitable that there must be some inferential assumptions made, though I will base them on data. Making an inference based on what hard facts are available is preferable to creating fantasies such as the mythical William Peter or Peter William Knight, son of Capt. Peter. Neither of those persons ever existed.

Finally, several years and many thousands of dollars later, this website is the result of a dedicated effort to find out the real deal on the Knights.

Now, having said that I used Peter Knight as the lynchpin for my searches forward and backward, let me say that the raw records will be presented chronologically as far as possible. The oldest material is actually what I researched last, but it goes at the beginning. It will include every type of record I have collected.

Along the way of collecting the records that most concerned me, along with the records of affiliates or associates, I came across some items that were so interesting or funny that I just had to include them as stand alones. I will note them in place.

The main thing to remember when reading this website, especially the records section which is the bulk of the material, is that it was put together to function as a simple, searchable database. It all exists in an Xcel spreadsheet where I can not only search, but organize by various factors. When I started compiling the records, I did not plan to publish it, I simply wanted to get everything together in chronological order to help me to sort and connect. I wanted to find where those darn Johns MUST connect.

The majority of the records come from published volumes of record collections as you will see from the bibliography. I transcribed everything by hand and, while I was doing it, I was making it suitable for searching. A record may have been written in archaic language, with odd spellings, including names, but I have rendered most of it into the modern, standard spelling along with names of associated persons. I didn’t want to spend half my time trying to figure out how something might have been spelled in order to perform a quick search and find it.

Sometimes, if I render the spelling the modern way, I will follow it immediately by the spelling that is in the text enclosed in parentheses such as “John Knight (Knyght)”.

You will find that I list records in this order: year, month, day, location, type, name; again, this is for searching and sorting purposes. If I pull out all the records pertaining to a given person, I want to be able to quickly organize them by year, and then location and type. I also want to be easily able to pull all records from a location to see who was associating with whom.

A goodly number of records provided by ancestry.com were used in the census, will and probate, and English parish searches. In most cases, in the early censuses, I read the entire census or parish record just to see who was around. (Families with connections of blood or friendship did tend to move together in groups.) Many of these records are difficult to read for a variety of reasons, not least of which was poor image quality on the part of the persons making and/or publishing the images. The main reason, however, was just simply the writing peculiarities of the scribe based on the conventions of the time, and the truly creative spelling that was going on in those days. When you put creative spelling together with writing peculiarities (conventional at the time), there is a lot of room for transcription error and ancestry.com apparently does not hire professional transcribers who are accustomed to dealing with such texts; a lot of them are really, really bad. I spent almost as much time sending error messages to ancestry.com, or correcting egregious transcription errors, as I spent transcribing names on a census!

When I encountered creative spelling of a name derived from ancestry.com, I correct it to the known or standard spelling automatically and most often, but not always, put in parenthesis the spelling on the record and I also add the ancestry transcriber’s version if it is clearly wrong or different from the actual record to signal that a researcher may have trouble finding the correct record because ancestry.com has not got it in their database in any suitable form. The following are examples of the text being correct but the ancestry transcriber wrong:

The following are examples of my correcting the original scribe and telling you what the original said:

The following are examples of me correcting both the original text and the transcriber:

My transcriptions of records are usually abbreviated to just the bare facts I needed for database/search purposes. Every record has a citation (with just a few exceptions) so that you can find it in the related book listed in the bibliography. Citations are of the form: (Name of author year published, p. #) In a few cases, I have put the publication directly with the record or as a footnote and not in the bibliography, such as in the case of a website (vetted) or a magazine issue or where I’ve read a photocopied image of a book page, or something along that line. Citations for ancestry.com are extremely difficult to give in any concise form so I simply use their source; not only that, but their search system is really, really bad. I’ve stumbled on records while searching for something unrelated, and then never been able to find them again even though I enter the exact details given by the record itself in their search form. Their search hierarchy is seriously flawed and even if you put in the correct, exact parameters, you may have to search patiently through hundreds of returns (or thousands), to find something useful. It still boggles my mind that I can enter the date of 1650 and get returns for 1925!

A very large selection of land transactions were taken from Volumes I through IV of Nell Marion Nugent’s monumental work of abstracting: Cavaliers and Pioneers. In those records, I just note something like (Nugent II, p. 25) I sometimes do the same with Coldham, Dorman, Fleet or McCartney who have produced some fairly massive works, as well as other well known and much referenced records specialists.

I have freely used Wikipedia for numerous informational items to fill in background; usually when I do that, I extract and condense and combine, and often re-write parts; it would be tedious and obstructive to cite every single clause or paragraph used this way, so I haven’t. You can get more details and the whole article about a topic with a simple search and I encourage you to do so on any given topic I put on the table! At the same time, I’ve used many other books to acquire background information that I use to supplement Wikipedia, and in my own writings here. As is normal in those parts, quotes will be properly attributed in place, and the various books I read for background are included in the bibliography.

Since location is so crucial for knowing who might be connected to who, I’ve constantly used online maps to get zoomed in and zoomed out views of a location that allow me to calculate rough distances between sites. I try to give that information as often as possible and encourage the reader to use maps liberally also! I'll be setting up a map search page via Google that should be helpful when I can get to it. But, be warned: the Knights were pretty mobile people and changed locations a lot! People got around in the old days a lot more than we might suspect!

I’ve tried to be as consistent as possible, as conscientious as possible, and as thorough as possible, but as they say, to err is human and this website is not going to be perfect no matter how hard I try; it’s a monster of an effort and I hope someone will come along and use it to refine our understanding of Knight genealogy and possibly help to add to the data. In the articles, I try to make it clear when I am speculating, and differentiate from when I am actually using records to make an argued case. I think the reader can tell the difference. Obviously, the further back in time something is, the more difficult it is to discern what was going on. I've written quite a bit on the historical background, and reading that in conjunction with reading wills down through the generations was a real eye-opener. There is nothing quite like reading wills to get the real scoop on the lives of our ancestors!

Finally, I very much hope that you, the reader, will feel the urge to understand our shared ancestors; I think they were most often totally awesome and furiously interesting people. With that in view, I urge you not to skip the historical background parts. You can skip them, of course, and just dive straight into the records and find out about your particular target person, but, unless you are a professional historian, your view of who these people were and why they did what they did will be profoundly impoverished.

When the colonists came to Virginia, it was the best of times and it was the worst of times and, having a bit of Native American and African ancestry myself (as probably all Colonial Virginia descendants do), I am hard-pressed to make any kind of judgment on any of the actors as groups, though certainly, there were egregious abuses by specific individuals in any of those groups; bad apples do not always spoil the entire barrel, but sometimes they do; and other times they only make it appear that it was all spoiled; you have to pick through things carefully and read with close and careful attention to find the truth. If you have read a lot of Colonial wills, or orders given in Orphans Courts, you will know exactly what I mean; the truth is stranger and more complex than fiction. And keep in mind that nobody emigrates from their home to a new and unknown place without pretty good reasons. Nowadays, the colonial settlers get blamed for emigrating; that only shows an extreme poverty of historical knowledge and understanding.

The main acknowledgements I want to make are to the often unsung heroes of genealogical research who got their hands dirty in the actual work of going to archives, reading and transcribing difficult texts, and making them available to armchair genealogists like myself. Yes, I’ve often compared one source against another and have found a few errors, but overall, their conscientiousness and care has been remarkable and I am humbled by their dedicated labors. I’ve also spent many, many hours reading through photographic images of ancient documents myself, sometimes with a magnifying glass, and sometimes utilizing image enhancing software to solve a tricky problem of script. I’ve cursed some scribes, and loved others, and I’ve made a few comments about that in the text. In fact, I’m going to share part of that process with you, the reader. I hope it will give you inspiration to do something similar, and perhaps some appreciation for what other transcribers have done, and maybe a little sympathy for the sufferings of those who are compelled to do such things by their infernal obsession with finding the facts.